- Home

- Holly Newcastle

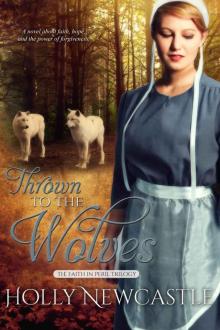

Thrown to the Wolves (The Faith in Peril Trilogy) Page 17

Thrown to the Wolves (The Faith in Peril Trilogy) Read online

Page 17

“No, the song. What are you humming?”

“‘In The Sweet By and By’.”

“You can sing it, if you want.”

The happy tune was one of my favorites. “All right.” Everyone said my voice was beautiful, and I enjoyed singing because it brought me such pleasure. “There’s a land that is fairer than day, and by faith we can see it afar; for the Father waits over the way, to prepare us a dwelling place there…”

I continued to work the flowers while singing, adding another to the daisy chain.

“In the sweet by and by, we shall meet on that beautiful shore, in the sweet by and by, we shall meet on that beautiful shore…”

When the last verse concluded, I stared at the flowers in my hand, noting a perfectly formed circle.

“Here you are. You may have this.” I handed him the small wreath.

He took the offering, his eyes on me. “Can you sing that again?”

I smiled. “Of course.”

“Over and over. Just keep singing it.”

“If you wish, Bishop Hartzler.”

“It’s just Elijah. We needn’t be so formal, not when we’re alone together.”

This implied a measure of intimacy, which caused my belly to flip over peculiarly. I began to sing, my voice lilting and steady, while he stared at the water. I adored this song, and, if he wanted to hear it a hundred times, I would oblige him.

“To our bountiful Father above, we will offer our tribute of praise, for the glorious gift of His love, and the blessings that hallow our days…”

Thunder threatened in the distance, while billowing storm clouds gathered. Elijah had fallen to his back, turning onto his side, facing away from me. His shoulders began to shake, and I knew he wept. I continued to sing, while he remained in this manner, wishing I could offer something more to ease his pain, but I had nothing else to give. Scooting nearer, I touched his back, rubbing gently. My voice rang out; the song had been repeated at least twenty times now.

He had stopped crying, because he no longer shook, and I continued to rub his back, until the last notes drifted away. A tiny drop of rain fell on my face. “We’re going to get wet soon.”

“I don’t know how I can face them.” He sounded miserable.

“You’re their bishop. They look to you for support.”

“I’ve got none to give. This life was never my calling.”

“Few people wish to lead the church, but you were chosen to do so, nonetheless.”

“I’m not in any position to … do this. I don’t know how.”

“Yes you do. You’ve done a find job since being ordained.”

“I doubt that.”

“You shouldn’t. I look forward to your sermons. You always speak of things in such a way I can understand them. They make sense. Whenever Bishop Graber preaches, my mind drifts off. His sermons aren’t all that inspiring.”

“You needn’t flatter me, Anna.” He lay on his side, looking away from me, with his hand beneath his head.

“I’m not. Everyone I know enjoys your sermons. It’s the one bright spot during church—those three long hours.”

“You’re just being kind.”

“No, I’m not.”

He turned, glancing at me, while a flash of lightning streaked in the distance. “I appreciate your support. Listening to you sing was … wonderful. It really was. It was so beautiful, so pure. I could listen to you … for hours.”

“Everyone says I have a gift.” I shrugged. “I don’t see it, but they seem to enjoy it.”

“I can always hear your voice among the singers on Sunday evenings. It’s so clear and beautiful and on pitch. You stand out, even if you don’t wish to.”

“Oh, drat. I’ll try not to be so loud.”

“That’s not what I meant.” He sat up, brushing grass from his jacket. His hat remained beside him, leaving strands of hair to blow in his face. The wind had begun to gust. “You're an asset to all the other singers.” He picked up the flower arrangement from the ground, examining it. “This is a work of art.”

“Now you’re flattering me. All children know how to make daisy chains.”

“But not this perfectly. Might I have it?”

“Of course.”

“It’s really lovely.” His gazed skimmed over me. “You’ve been very helpful, Anna. I was feeling … dreadful earlier, like I wanted to … end it all. I really did. I kept thinking, what’s the purpose of going on? I’ve lost the only woman I’ve ever loved and all the babies we … ever had.” He shrugged. “There’s really no point in it all.”

“I disagree. Might I speak plainly, Elijah?”

“Don't you always?”

“No. I hold back quite a bit of what I’m really thinking.”

“I’d like to know what you’re thinking.”

“You may not want to hear this.”

“Try me. You’re looking at a man who’s got nothing to lose. I doubt your words could ever hurt as badly as what I’ve been through.”

He had a point there. “You’re needed, Bishop Hartzler. People count on you to be their spiritual leader. They look up to you, whether you like it or not. We need you for baptisms, weddings, and funerals. We need you to console us, to just be with us. I know you’re suffering, but we aren’t the enemy. You don’t have to tie sheets together to escape us. Everyone is here to share your burden, not cause you more anguish. Your grief has clouded your judgment, but I can understand it.”

He seemed thoughtful. “That’s the worst you have to say?”

“No.”

“What else? Don’t hold back. I’m not a fragile flower. I won’t break.”

“I … think … you’re in a great deal of self-pity. I can understand it, but I hope it’s of short duration. It’s a very selfish place to be. You’re not the only one suffering in our community. We’re all brought to our knees at one time or another, but it’s how we get up that matters. Everyone’s watching to see how you pull yourself together. That’s how they’ll judge you, I’m afraid.”

I worried I had overstepped the boundaries and offended him. He grew quiet for a long while, as the wind picked up, bringing the pungent aroma of manure. The fields had been fertilized earlier in the season, and the rain in the distance brought out the smell. That rain would be here soon enough.

He sighed deeply. “You’re right.”

“You asked for my opinion. I’m sorry, if it upset you.”

“No, you’re fine. I needed to hear that. Everything you said was … right. I’ve been lost in self-pity. That much is true. I want to shut everyone out. I wish they’d all go away, but they won’t.” He patted my hand. “I’m guilty of everything you’ve accused me of.”

“I didn’t accuse you, sir. I’m only saying what I think I see. I might be wrong about it all.” He had lost everything dearest to him these last twenty-four hours, and I had heaped more blame on him. I probably should not have been so open. “I think you’re forgiven for this time anyhow. It’s your right to grieve the way you see fit. I just don’t want you to think that you’re a poor bishop, because you aren’t. You’re a wonderful preacher. You’ve a great deal to offer our district. Never think otherwise.”

He wrapped his arms around his legs, resting his chin on a knee. Although older than me by at least six years, he looked entirely young then.

“How can I guide them … when I feel so weak? I feel … empty. It’s like taking a knife and gutting a pig. There’s nothing left inside.”

“The only thing I can think of is to pray for strength. He will help you, if you ask.”

“What if I’m angry with Him? What if I want to curse Him and cast him from my life?”

“That’s the grief. It’s your pain making you feel that way. Time will make it easier.”

“What I just said … I’ve never told anyone. No one.” He met my gaze. “It’s almost blasphemous, you know.”

“I won’t repeat a single word, sir.”

“E

lijah.”

“Elijah.” It dawned on me that I liked that name a great deal.

A rumble of thunder had us glancing into the distance, as the wind gusted, moving the cornstalks almost violently.

“We must go back,” he said.

“We’re about to be doused.” I got to my feet. “Are you feeling any better now? You won’t tie rocks to your ankles and fling yourself in the pond, will you?” I had been far too blunt again, regretting those words instantly. “Oh, dear … I mean—”

He shocked me by smiling. “I do appreciate honesty. It’s rare in a woman, well, one you’re not married to. The younger ladies say only what they think we want to hear.”

“I’m sorry. That was badly done.” Droplets of rain hit my face. “I shouldn’t have said that.”

“It’s fine, but we need to go, Anna. We have to hurry or we’ll be drenched.” He snatched his the hat off the ground, placing it on his head.

“You’re not angry with me?” We hurried down a lane, heading towards the vegetable garden. The house loomed in the distance. A lamp had been lit, as a yellow glow shone through the kitchen window.

“I’m not mad. You’ve been extremely helpful—again.” We neared the privy, the roof overhung by three feet. The clouds had opened up at that moment, and we lingered by the outhouse, pausing before going further. “You’re a wise young woman.”

I shrugged. “Not really. It’s just what Mam would say. I can’t take credit for any of it.”

“And modest.”

“Hardly. I have a vain streak that would shock you.”

“How so?”

“I stare at myself in glass whenever I’m able. I’ve even considered buying a small piece of mirror, but I’d have to hide it. I want to see the color of my eyes. I know they’re blue.”

“Bluish gray.”

“I can’t see that.”

“With lots of lashes all around. You’re a very pretty girl.”

This compliment left me dumbstruck, my tongue faltering. “Oh … I …”

“Now I’ve embarrassed you. I’m sorry.” He glanced at the house. “It’s ten yards or so. If we wait much longer, it might be worse.”

“Then we should run.”

“Wait.” His hand fell to my shoulder. “Thank you, Anna. Thank you for talking to me. You made me step outside myself for a moment. I … am ashamed for escaping through the bedroom window. I …” he looked sheepish … “I behaved like a youth during Rumspringa. My friends and I would drink whiskey and jump off roofs into hay bales. We were a wayward bunch, but we managed to pull ourselves together to be properly baptized.”

“At least you didn’t break your neck.”

He squeezed my shoulder gently. “I’m going to do better. I’ll let them help me. You’re right about everything. I won’t close myself off again. I promise.”

Those words gladdened me. “It’ll be easier after the funeral. You’ll have plenty of time alone. Maybe too much.”

“Will you visit?”

The wind had whipped several strands of hair free, and they flew into my face. “Of course.”

He smiled gratefully. “Then perhaps I shall make it through.” He held his hat. “Are you ready? It’s a mad dash to the finish.”

“Yes, sir. I am.”

“That makes me feel so old, Anna.”

“Elijah. Yes. I’m ready.”

“We’re going to get wet.”

“It’ll dry in time.”

“All right. Let’s go!”

We took off running at full speed, racing through the vegetable garden to the kitchen, where people had seen us coming. They flung open the door. The aroma of something delicious baking assailed me along with the scent of coffee. Mam and Ruth had seen my approach, and they gathered around me, while Bishop Hartzler found himself amongst his family, who gave him a towel to dry himself. He glanced my way for a brief second, and our eyes met. I felt I knew him quite well now, even some secrets from his wild, running around years. We had formed a connection—a friendship. This knowledge manifested in a pleasing, nearly euphoric feeling.

“Where did you go?” asked Ruth.

“To the outhouse, but Bishop Hartzler was there. We talked for a while.”

“You’re wet, my dear,” said Mam. A boom of thunder rumbled over our heads, the house shaking from the impact. Lightning had hit nearby. “It’s a good thing you came in when you did.”

“I’m fine.” She had given me a small towel. “You needn’t fuss.”

“Everyone was wondering what happened to Bishop Hartzler.” Ruth glanced over her shoulder at him. “Someone said he tied linen together and climbed out the upstairs window, but that seems too farfetched to believe.”

“He did.” I had lowered my voice, as there were people milling about. “He escaped his own house.”

Mam seemed confused. “Why would he do that?”

“I asked him the same question. I think he’s overwhelmed by it all. He’s not managing his emotions very well, but our talk helped.”

“You were out by the privy?” asked Mam.

“No. We went to the pond. We sat there until the rain began.”

She appeared thoughtful, glancing over her shoulder at Elijah, who drank a cup of tea. “I see.”

“I promised not to reveal his secrets, but, suffice it to say, he’s going to try not to exclude everyone. It’s hard for him. He’s a private person. You know how nosy people can be. Everyone in the district knows everything about everyone.” Privacy was a luxury.

“That’s true.”

“So, I talked him into coming back. He’s going to try not to shut people out.”

“He doesn’t have an issue with you, though. He’s more than happy to talk to you.”

“I’m not his family or related to the Beachys. I’m impartial.”

“Yes.”

Ruth did not find our conversation interesting, as she had disappeared into the other room. Catherine Albrecht appeared in the doorway, her eyes settling on Elijah. She beamed happily at his sudden appearance.

“We were so worried.” She spoke in a slightly nasal sounding voice. “You scared us to pieces.”

I had not realized I scowled, until Mam said, “You’re jealous of Catherine, aren’t you?”

“What? Goodness, no. Why on earth would I be jealous?”

“Because she’s fawning all over the bishop.”

“Well, she’s … um … an unmarried woman, and he’s … without a wife now, although he’ll have to mourn for the appropriate amount of time. Perhaps he wants a … doting, second wife.” I found watching them difficult, because she flitted around him, drying his hair and making sure his tea was warm enough. I did not want to see this. “Where’s Rebekah?”

“In the parlor.”

“I’m … I think I’ll talk to her.”

Mam grinned sympathetically. “Abram Zug is here as well. They just arrived.”

“How nice. I’ll go see him.” My voice sounded strange to my own ears. I had to force myself to sound happy, relieved, and encouraged. I didn’t want to quit the kitchen, wishing I could sit next to Elijah, but his parents, brothers and sisters flanked him now, with Catherine hovering servilely.

I wove my way through the throng, leaving Mam behind. Rebekah spoke with Mrs. Shetter, while Ruth and a friend gazed out the window. The storm continued to rage, the wind and rain lashing against the glass panes. Abram saw me at once, hastening over. His parents were near the door in conversation. I wasn’t fond of this room because it held two caskets, one for Justine and another for the baby.

“There you are.”

“Hello, Abram.”

He smiled politely. “What a tragedy. We’re hardly believing such sad fortune happened again.”

“It was shocking and unpleasant for everyone.”

“Have you eaten yet?” He glanced over my shoulder at the kitchen. “It smells quite nice.”

“There are lots of pies and things.”

“I’m sure that’ll be appreciated.”

The Beachys sat on the sofa, while Mrs. Beachy held a handkerchief to her nose. She looked like she had been crying.

“Do you have any idea when we’re going to eat?” He eyed me hopefully.

“Um … I … think soon. We have to say prayers first.”

“Oh, yes, of course.”

It dawned on me then that our conversations were never truly personal. We spoke on a simple, superficial level—about the weather, farming, or food. He had never said anything about his escapades during his Rumspringa years. Women did not participate in such behavior or shenanigans. Most young ladies easily accepted their position in the Amish faith without having to push the boundaries like men.

Movement in the doorway caught my attention, as Elijah appeared. “Hello, everyone. We’re going to eat soon.” He glanced around the room, his eyes falling upon me. Then he stared at Abram. “Thank you all for coming. You’ve taken time away from your families and farms to commiserate with me. I … will endeavor to be worthy of this sacrifice.” Then he stared at the coffins. “Justine wouldn’t want anyone to make a fuss over her, but … well, we thank you for being here.”

Mrs. Beachy got to her feet, and I feared there would be a scene. Elijah had done his best to accept the dozens of people that had come to pay their respects, even though he wished to be alone. But, just yesterday, in his grief, he had pointed a loaded rifle at his mother-in-law. I held my breath, worried about what might happen.

“Will you lead the prayer, Elijah?” she asked.

He nodded soberly. “Yes.”

“I want you to know I’ve forgiven you for nearly killing me.”

The room silenced to such a degree, the only noise came from the sound of rain pounding against the roof. We all held our breath in anticipation. What would he say now?

“I’m sorry about that, Fannie. That was wrong of me. I wasn’t in my right mind. Thank you for forgiving me.”

It seemed as if everyone in the room took a collective breath, relieved there would not be another unpleasant event.

Mrs. Beachy cleared her throat. “Then we may put this behind us. I … behaved badly too. I wasn’t without fault. This has been very difficult.”

Thrown to the Wolves (The Faith in Peril Trilogy)

Thrown to the Wolves (The Faith in Peril Trilogy)